Impostor syndrome: How do we break out of the cycle?

May 28, 2025 | General

You’ve probably heard of the term “impostor syndrome”, as it became a buzzword in recent years. But the concept has been around for over four decades: it can be traced back to a paper by Clance & Imes in 1978. At the time, impostor syndrome was considered a phenomenon among high achieving women. Today, people of all genders and occupations resonate with it, and report having experienced it in the past or to live with it every day (Huecker et al., 2023). But what is this phenomenon? Why do we get it? And is self-doubt always a bad thing?

What is impostor syndrome?

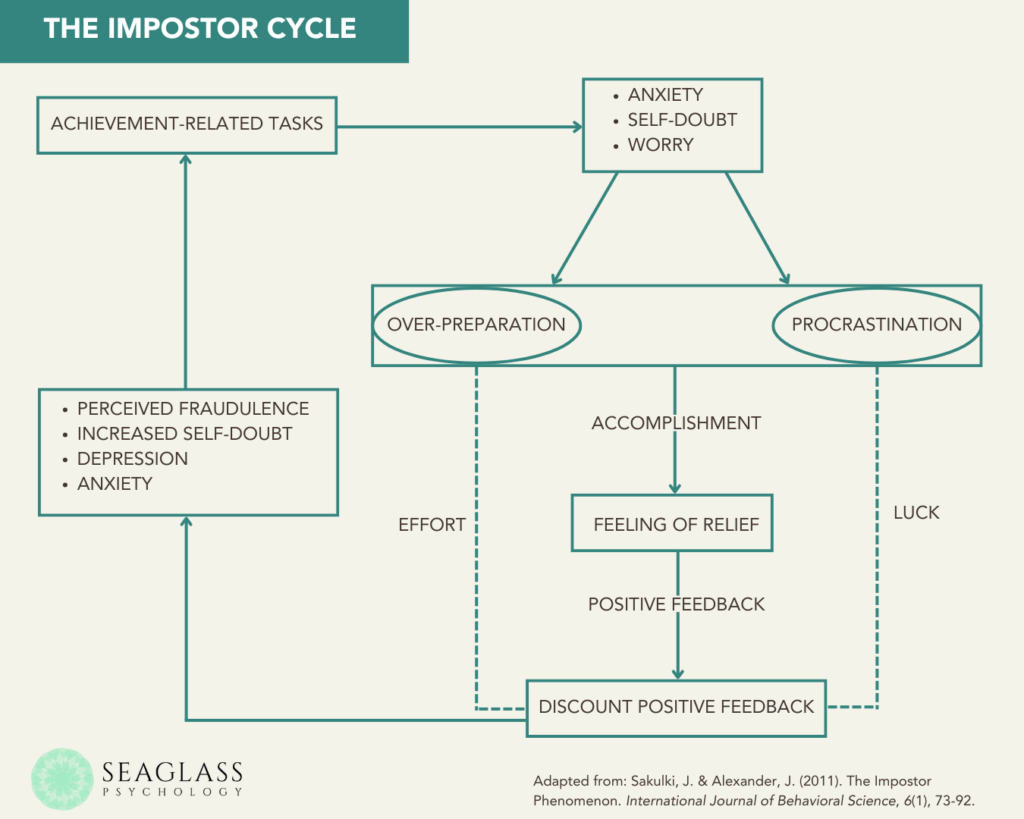

A key component of impostor syndrome is the inability to internalize our achievements, despite external proof of our competence. This tension can lead to a pattern of personal experience, which Sakulki & Alexander (2011) summarized as a cycle:

Why do we end up in this pattern? As usual with mental health, a mix of internal and external factors come into play. Issues like our genetic imprint, temperament, and other individual proclivities, as well as how we were raised, our primary cultural backgrounds, and other social experiences, help shape how we see ourselves in relation to the environment. As the impostor syndrome cycle is self-reinforcing, over time, the pattern becomes entrenched and hard to break. Eventually, seeing ourselves as fraudulent in a high achieving environment can lead to other problems, like low self-worth, chronic stress and anxiety, and depression.

Recognizing impostor syndrome

Generally, there are five accepted, interrelated characteristics of impostor syndrome (Huecker et al., 2023):

- Perfectionism: Demanding standards for our work that are often unattainable.

- Super-heroism: A need to appear overly prepared and competent.

- Fear of failure: Anxiety over the possibility of failure or shame, which interrupts our capacity to engage with a task.

- Denial of competence and capability: Difficulty with acknowledging our intelligence, experience, skills, and natural talent. This may be reflected in a tendency to internalize failures (I failed because of me) and externalize successes (I did this well because I had help/I was lucky).

- Fear of success: Worry over how things may change if we are consistently and reliably good at something, like having higher demands placed on us.

In other words, and according to Young (n.d.), this phenomenon comes down to:

- a skewed perception of what it means to be competent;

- an unhelpful response to mistakes, setbacks, and constructive feedback;

- and the false belief that if we were really competent, we would never experience self doubt.

The importance of context

Even though impostor syndrome isn’t a psychiatric condition, it is widely considered as a very real internal experience. Historically, it was studied in cis women in the workplace, college students, and people in healthcare occupations, which limited our understanding. Nowadays, we know that people with other identities and intersections can struggle with perceiving themselves as a fraud as well (Huecker et al., 2023; Bravata et al., 2020).

Today the concept of impostor syndrome is in flux. It’s important to remember the systemic pressures that may lead someone to doubt their competence. From organizational culture to larger social issues such as patriarchy, colonialism, and racism, having experienced bias, prejudice, and exclusion may reinforce the lack of confidence inherent to the impostor phenomenon (Tulshyan & Burey, 2021).

Finally, just like with anxiety and stress, we may consider that there’s a way to experience self-doubt that is functional. We all need to be able to question our self-perception. If someone can’t contemplate on the areas in which they could grow, they would be unable to get better for their own and others’ benefit. What makes a difference is how stuck we are in these responses, and how much they interrupt our life and affect it negatively.

How do we recognize if our experience is functional and helpful, instead of unhelpful? Whether it’s anxiety, stress, or self-doubt, we say that it’s functional when it’s actionable and finite. Here’s an example to help you visualize this:

- Helpful self-doubt: I thought I was being smart by overpreparing, but it’s just so exhausting. Maybe my approach hasn’t been as helpful as I thought. Could I find a different way to do things?

- Unhelpful self-doubt: Maybe I’m just terrible at my job, and people don’t tell me what they think out of pity

Getting out of the cycle

To break out of the patterns that lead to the impostor syndrome cycle, we must be able to observe ourselves, assess our wellbeing, and act according to our needs and goals. We do this by developing our capacity to perceive what is present inside of us and around us, without prejudice.

When we open up to observing without judgment, we’re able to see our self-doubt as information. Then, we can make the best decisions about how to address our needs and how to take action to manage our mental health.

If you’re interested in developing self-exploration as a skill, get in touch to learn more about working with me.

I grew up speaking Spanish. English is my second language. When I communicate in English, I make mistakes. I've chosen to let the writing on my blog reflect the kind of mistakes I make when speaking, so that you have an idea of what it might feel like to talk to me. I trust the message is still clear but, if it's not, please don't hesitate to ask me for clarification.

The information provided on my blog is a mix of my personal thoughts, professional approach, and articles related to mental health. The purpose of sharing all of this is to communicate the models at the core of my practice, as well as to provide education. I hope this will help to minimize some of the power imbalances related to my profession. The articles on this blog should not be considered as professional advice for any one person or group of people. If you have any questions about the appropriateness of this content for you, please contact a qualified mental health professional.